“WALKABILITY: A Street Is A Terrible Thing To Waste,”

New York State Conference of Mayors Summer Bulletin

The photos and captions below accompany my article “Walkability, A Street Is A Terrible Thing To Waste” in the Summer 2014 Muncipal Bulletin of the New York State Conference of Mayors (NYCOM).

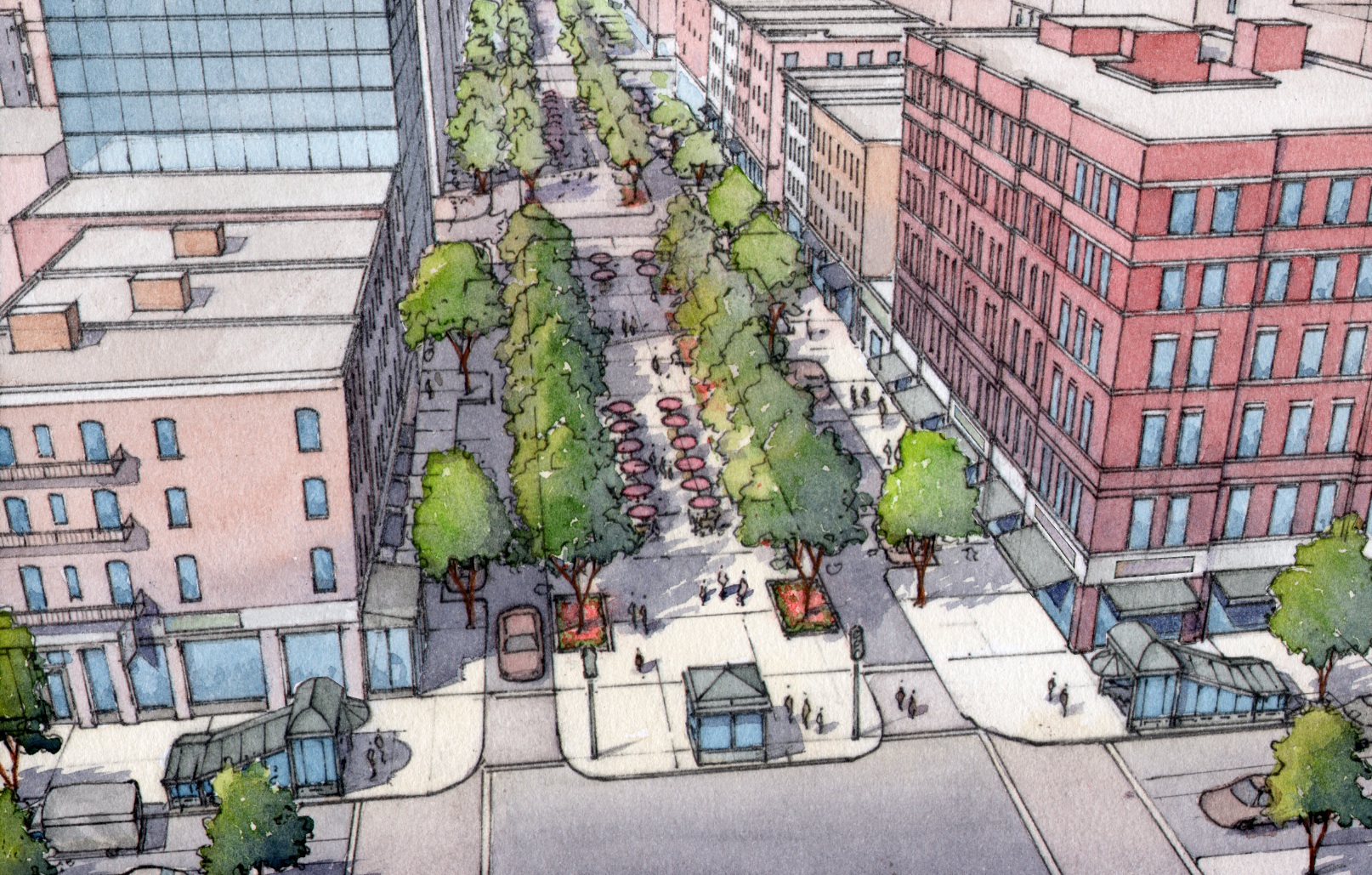

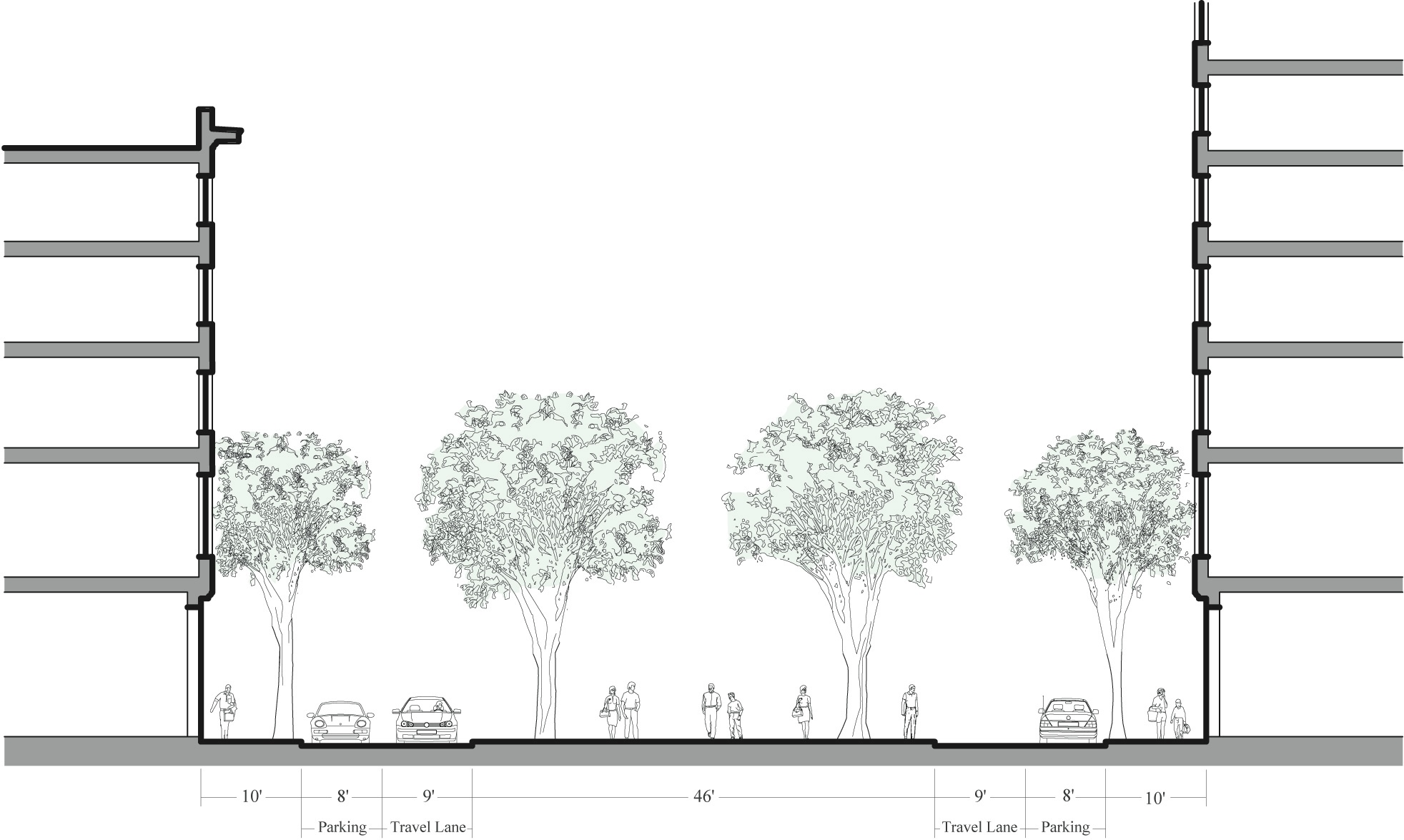

The Yorkville Promenade is a proposal made in 2011 by John Massengale and Victor Dover, co-authors of Street Design, The Secret to Great Cities and Towns, for changes to Second Avenue in Manhattan after the completion of the Second Avenue subway. Eighty percent of Manhattanites don’t own cars, and Second Avenue is the main shopping and outdoor dining street of the Upper East Side, yet it is slated to be a one-way, suburban-style arterial (with bicycle and bus lanes) that will make it easy for suburbanites to drive in and out of the city. This proposal calls instead for wide sidewalks, two narrow and slow traffic lanes with short-term parking, and a central promenade that could be filled with tables for cafés and outdoor dining, much like parts of the Paseo de Gracia in Barcelona, Spain.

Achieving the goals of the Vision Zero pledge signed by Mayor de Blasio will require building on and advancing the groundbreaking work of the New York City DOT under Mayor Bloomberg and DOT Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan in places like Times Square and Madison Square. The city will need new roads with design speeds that support the 25 mile per hour speed limit recently adopted by the city, and the new, slower streets give the opportunity to make more places in New York that begin with the goal of walkability and pedestrian comfort rather than traffic flow.

Massengale and Dover chose Second Avenue for the proposal for three reasons: the new subway will increase foot traffic and development in the area; the street was dug up for the subway construction and it will need to be rebuilt, which means that the usual reservations about the cost of moving curbs and the like do not apply; and the dining and entertainment streets on the Upper East Side are one-way arterials with fast, noisy, and polluting traffic. A promenade street would bring a commercial boom to this formerly blue-collar section of the Upper East Side, which lacks the comfortable small blocks and access to Central Park farther west in the neighborhood. Studies show that the traffic induced by the current one-way arterial would both decrease and merge into the surrounding grid. Until the 1950s and 1960s, all Manhattan avenues were two-way. Many should be again.

New York City is unlike any other town or city in New York State. But all towns and cities that want their centers and downtowns to be walkable need to consider plans that put aside the idea that quick and easy traffic flow should be the overriding goal in all street design. This particularly applies to municipalities that want to reduce pedestrian deaths, because rapid traffic flow is incompatible with safe places for pedestrians.

Rebuilt with Complete Street funds, this archetypal arterial with new bicycle lanes, sidewalks, and a painted “road diet” is better for local residents than it was before the changes. But the thoroughfare is still an old-style, auto-scale street where few pedestrians or cyclists will feel comfortable, and the design of the street will not make drivers go slowly.

The street illustrates the point that Complete Street legislation mandates better streets without showing how to make streets where people want to be. A problem faced by the walkable places in our downtowns and town centers is that the suburban-style Complete Street shown above is frequently proposed for walkable places, where we need radically different pedestrian-friendly designs. When Complete Streets are combined with Vision Zero goals for reducing fatalities, walkability and better urban design easily follow.

The image above is a Google Maps street view of Second Avenue, looking south from 86th Street. New Yorkers pay a lot money to rent or buy small apartments near Second Avenue, because they want to enjoy the public life of the city. That takes place in the public realm, or what Jan Gehl accurately calls “the space between the buildings.” But three-quarters of the locals don’t own cars, and most of the space between the buildings has been given to cars belonging to out-of-towners who are driving through Yorkville, rather than to Yorkville.

Many Main Streets in small towns upstate share similar problems, particularly when their Main Streets are also state highways. Roads built for King Car kill the pedestrian experience and sometimes literally the pedestrians, because the design speed of the roads encourages drivers to go too fast for pedestrian safety. All places that want pedestrians to get out of their cars and walk around need safer street designs. The good news is that these are compatible with better urban design and platemaking.

Lancaster is a sprawling city of 150,000 approximately 70 miles north of downtown Los Angeles. Moule & Polyzoides turned an auto sewer in the center of the city into the newly named The Boulevard. The multi-functional central median is sometimes a parking lot, sometimes a promenade, and sometimes the setting for markets and fairs. The result was a major increase in downtown property values and an 85% decline in personal injuries.

Above, a view of The Boulevard before it was reconfigured to make it a more urban and pedestrian friendly street. Below, reclaiming the space between the buildings for the public realm and public life.

I include these views of the intersection of Lexington Avenue and 89th Street in 1913 and 2013, because they show that even in Manhattan, where 80% of the residents don’t own cars, the car is still the king of the public realm. The earlier photo was taken during the construction of the East Side IRT subway, which is why the sidewalk is covered with planks.

The later photo shows the results of the street widenings that took place on almost all the avenues in Manhattan during the 1950s and 1960s. All the north-south avenues on the island were two-way streets until then, but with the exception of a small number of places, they were turned into one-way arterials, to make it easier for suburbanites to drive in and out of the city. At the same time, the pedestrian experience was significantly worsened, as seen in the photo above.

When you look closely, you see it is even worse than originally imagined, because you see that the light well at the corner was filled in and the stoops on the rowhouses were removed. The sidewalk is probably less than a third of its original width. The owners of the historically significant houses, designed by the architect of the Plaza Hotel, probably got in their cars and drove on the new arterials to new houses in the suburbs.

Remember that this all happened 1) on a street where most people don’t own a car, 2) on a street with the busiest subway line in America running beneath it, and 3) just a block away from the commuter rail under Park Avenue that is probably the best commuter rail in the country. The fact that King Car was rammed through this neighborhood on this street in New York City shows how far we put the easy flow of traffic above all other considerations.

In the 1950s and 1960s, we brought suburban-style arterials into the city. Today, we are bringing suburban-style traffic calming into the city. The end result is only slightly better.

In the 1990s, Federal regulations mandated the hiring of pedestrian specialists in every state. These specialists worked with Department of Transportation engineers to improve the lot of the pedestrian. Most of their work was in the suburbs, because that is where building was happening in the 1990s in America. Much of their work was on streets where there was little reason to walk and where few people wanted to walk. In that context, it makes sense that a painted Road Diet, for example, is better than what came before.

You see some of this in Long Beach, California. Long Beach is a real city (sometimes called “the Brooklyn of Los Angeles”) with a good downtown. It has a wonderful climate for being outdoors, and in recent years the city has made a major effort to provide bicycle lanes for its residents.

Photo-realistic renderings for the transformation of Fairfax Boulevard in Northern Virginia.

Click here to view a short video of Seven Dials. © 2014 Ben Hamilton-Baillie

Many think that “shared spaces” — where pedestrians, bicycles, cars, and trucks all have equal status — will never work in America. They’re probably right that there are few places in the country where that would be accepted today (although there are exceptions*). Shared spaces do work well in Amsterdam, but the Dutch probably have a more homogenous culture than us, their roads are covered with bicycle traffic (which forces cars to accommodate them), and the Dutch have been working on taking their streets back from the car since the 1960s.

The Dutch traffic engineer Hans Monderman was a pioneer of shared space. He noticed over time that the more he took signs and markings off the street, the slower cars went. Eventually he took them all away, and he used to famously demonstrate that he could walk backwards into the shared spaces he made without being hit by a car. Today, many Dutch cities large and small have streets with no traffic signs, traffic lights, or paint on the road, just as all American cities had 100 years ago, before “Organized Motordom” (a coalition of car companies, oil companies, and others like the young American Automobile Association) realized that selling more cars would require claiming our streets for the unimpeded flow of cars.

I have a video here that shows the way New Yorkers used Broadway 100 years ago, very similar to the way the British use Seven Dials today. Everyone slows down to much more than the speed of walking, and drivers either have to catch the eye of pedestrians and “negotiate” who goes first—or failing that, simply give the pedestrian preference.

American engineers haven’t paid much attention to Monderman, because his free-range pedestrian approach is the opposite of the free-range auto approach implicit in most of their work. American urban designers haven’t paid much more than lip service to Monderman, probably because he’s not much of a placemaker. If you visit his work, as we did for the book, there’s not much there there. His shared spaces function well, but they don’t attract people to them, because he doesn’t pay much attention to what makes a space a place where people want to be. Visually, they’re not very interesting, and he can use so many different pavers that they pull your attention away from the space of the street, without much reward. That corresponds to very little attention to making a defined, comfortable space.

There are a few places in New York City that might be good shared space. Gansevoort Square is one: it was brought halfway to that use in a reincarnation under the Bloomberg administration. Broad Street, which was closed to most traffic after 911, is another, and perhaps even Lafayette Street is one. In Street Design, we proposed a shared space we called Jane Jacobs Square, because it was near her old house on Hudson Street. An interesting triangular space at the heart of the original Greenwich Village, it’s an interesting triangular space where two grids that are not quite parallel come together.

Tactical Urbanism—using temporary, inexpensive methods to show possible changes—may convince Americans that there are places here for shared space. People have used Tactical Urbanism around the country to show the value of changes. Tactical urbanism frequently involves temporarily taking pieces of the street away from auto use, and sometimes produces ad hoc shared space that people discover they like.

——-

* Seaside, Florida, the first “New Urban” development in America, is one. I was Town Architect there in 1986. Time magazine gave it a Best of the Decade award and called it “one of the most influential projects of the decade, and, hopefully, decades to come.” All of the streets in Seaside other than County Road 30-A have narrow, brick roadways with no sidewalks and parking outside the bricks. Everyone walks in the road, and cars have to slow down accordingly.

There are also narrow streets here and there, like Espanola Way in Miami Beach, that are taken over by pedestrians but where cars are still allowed. Drivers have no choice but to move at the speed of the pedestrians walking in flip flops.